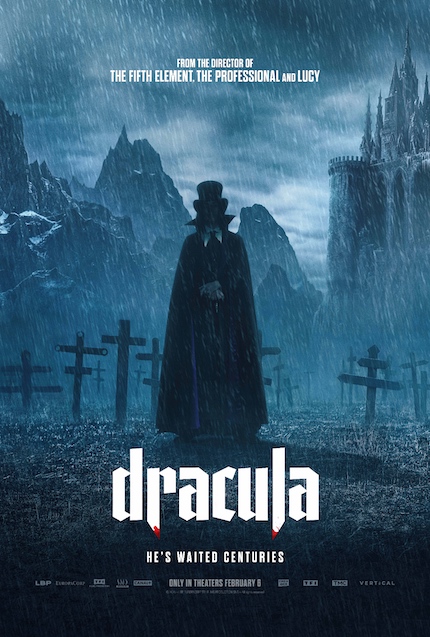

Caleb Landry Jones and Christoph Waltz star, with Zoë Bleu and Matilda De Angelis in vivid support. Luc Besson wrote and directed.

In Luc Besson’s Dracula, the titular character is an incurable romantic, still yearning for his one true love after 400 years.

Prince Vlad (Caleb Landry Jones) and Princess Elisabeta (Zoë Bleu, aka Rosanna Arquette’s daughter and also the uncredited Vampire Queen in the Lifetime TV movie Mother, May I Sleep with Danger?, 2016) are enjoying connubial bliss when the Prince’s men arrive to drag him away to battle.

On the way, the Prince makes the necessary stop by the local Cardinal to ask for his blessing, though he makes known his reluctance by asking if the battle is truly necessary. If it is, sure, he says, I’ll kill all the hundreds of men I’ll probably have to kill, but please ask God to protect the life of my wife.

With that out of the way, he and his men kill the anticipated thousands — or as many as the movie’s budget will allow — but then the Prince is informed that the Enemy has dispatched a unit of soldiers to attack his princely castle; the Princess fled for her life. The Princess gives furious chase and catches up. Unfortunately, one imprecise sword throw later, and he has inadvertently killed his own wife.

Blaming God — and neglecting to mention his own culpability — the Prince demands that his wife be restored to life. When his demand is not met, the Prince kills the Cardinal and vows his rejection of God.

Four hundred years later …

A priest with a particular set of skills (Christoph Waltz) is dispatched from Rome to Paris to deal with a wild woman named Maria (Matilda De Angelis), who has been chained up under the ‘care’ of puzzled Doctor Dumont (Guillaume de Tonquédec). After a careful examination, in which Maria responds very positively to three drops of blood, the priest declares that she is a vampire.

Meanwhile, in Romania, Jonathan (Ewins Abid) has arrived at the castle of Vlad (Caleb Landry Jones, looking suspiciously like Gary Oldman in Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula, 1992) and becomes increasingly curious about Vlad’s unusual behavior, leading to him being chained up under the ‘care’ of Vlad and his gargoyles come to life. In a desperate bid to stay alive, Jonathan asks Vlad to tell his truth or, at least, tell him how he has been spending the last 400 years. Vlad says, OK, have I got a story for you!

Often riotously entertaining, and just as often simply ludicrous, Luc Besson’s Dracula finds its true strength in its (reportedly) original title: Dracula: A Love Tale. At its heart, that’s what the film seeks to be: a simple romance about a guy and a girl, separated by circumstances beyond their control.

What complicates things is all that vampire lore, some of which writer/director Besson includes and/or tweaks, and some of which he dispenses with whenever it becomes inconvenient or doesn’t fit the story he wants to tell. As a result, the film’s tone wavers, though most often it sticks to straight dramatic narrative, coupled with highly-peopled action sequences and florid flashbacks.

Sometimes it becomes silly, whether intentional or not, as when the bereaved Prince attempts suicide by jumping out of his castle multiple times, without success; only for it to be revealed that he has been jumping into a deep bank of snow. Other times, for example, Christoph Waltz’s droll delivery of his lines is clearly intended to be wryly amusing (and it is).

Still, Besson never lingers on the bloody carnage that Vlad wreaks upon innocent victims. Nor do he make his atmospherics carnivalesque and gothic, like Coppola’s version. Instead, his intentions become more clear when Waltz’s priest explains to Jonathan, who has escaped from Vlad’s clutches, that salvation is available from God to any who express true repentance, including Vlad.

And so the whole of Act III is largely devoted to Waltz’s priest searching for Vlad so he can lead him to repentance. Whether the priest believes this or just wants Vlad to believe and allow himself to be vanquished doesn’t really matter.

It is, though, the message that writer/director Luc Besson, who has faced serious legal charges in the past and, as of 2018, has been cleared of them, wants to convey: it is possible for your past to no longer play a role in your future. Whether you believe that or not, his Dracula makes a convincing case that Bram Stoker’s novel, first published in 1897, is still relevant material for modern audiences, just as much as Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein has proven for Mary Shelley’s novel, first published in 1818.

The film opens Friday, February 6, only in movie theaters, via Vertical Entertainment.