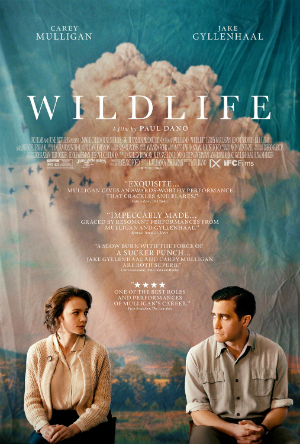

Raging in the Montana distance of actor turned director Paul Dano’s debut feature Wildlife is a forest fire.

Raging in the Montana distance of actor turned director Paul Dano’s debut feature Wildlife is a forest fire.

It’s something his troubled and emotionally stunted father (Jake Gyllenhaal) believes he must go and fight in order to quiet “the hum” in his head. And when wife and mother Jeanette (Carey Mulligan) decides to drive their confused teenage son (Ed Oxenbould) right up to the doorstep of the raging inferno so he can glimpse the entity that has pulled his father away from their lower middle class world, she talks about how certain animals run while others get confused by the smoke and end up being burned alive.

It’s this confusion that seems to inflict people, too, as the film’s 1950s era-set nuclear family slowly dissolves at the seams, writhing and throwing themselves into one disorienting scenario after another. What initially looks like cathartic independence for young and commanding wife Jeanette soon comes to resemble the wildlife unable to differentiate their environment from an all enveloping fire. It may sound like an easy analogy for a film to make, but Dano’s command of the material is anything but complacent.

From the outset, Wildlife adapts its point of view from the juvenile gaze of Joe, portrayed well by Australian actor Oxenbould, who even looks and feels like a young Paul Dano. Watching his parents casually flirt around the kitchen table or being obscured from their more volatile moments, yet acutely aware of their tense ramifications, we sense something isn’t right with father Jerry from the beginning.

Summarily fired from his job at a country club, things go from bad to sour. Jerry says he’s looking for a job, but spends his days getting drunk and sleeping in his car, where’s he’s naturally discovered by his son.

When Jerry suddenly announces he’s leaving to join a roughneck group of firefighters to battle a blaze in the big sky country on the outskirts of town, Jeanette reverses the usual expectations of the doting, respectful wife of the 50s melodrama and places the burden of the world (and her own womanhood) on her broad shoulders, finding full-time work and carrying on as if her husband has left for good.

The most complicated aspect of Wildlife comes in this portion of the film, when Jeanette begins a relationship with a much older, wealthy man in town named Warren (Bill Camp). In a carefully composed and nervously-timed dinner party scene between his mother and Warren, Joe is forced to grow up very quickly with what he hears and sees. It’s here that Mulligan’s performance comes full circle, embodying a woman shaking with misplaced anger and yes, confusion. The range of emotions that swirl over her face and the sheer dread that engulfs the viewer during this scene not only establishes the high point of the film, but crystallizes Dano’s sensitivity as a burgeoning talent behind the camera as well.

Not content to stop there, Wildlife sets up even more tense situations when Jerry re-emerges into their lives and discovers the newfound independence his wife has discovered. Like all good, smoldering, repressed 50s-era dramas, the violence and anger that so often lives just beneath the surface rears its ugly head.

And repression is the dominant force of many films in the past decade or so that have placed a revisionist lens on the Douglas Sirk dramas of the last mid century. Todd Haynes’ Far From Heaven (2002) and the many adaptations of Philip Roth novels about ‘stifled Americana’ have come and gone with varied results.

Where Wildlife follows the same template of American life souring in a decade we’re often told was the epitome of American blossoming, it also succeeds due to its deft handling of emotions and situations. There are no easy answers and complicated personalities don’t parse their feelings in digestible pieces of dialogue. Co-written by fellow actress Zoe Kazan and adapted from a Richard Ford novel of the same name, Wildlife thrills because of the extremely believable and precise cast. We’re accustomed to Carey Mulligan turning in a standout performance, but her role as Jeanette is one of her finest yet and Gyllenhaal imbues Jerry with a deep-seated wandering that feels palpable for a man of the 50s who just can’t cope with the conformity that’s expected of him.

Though it spends a great deal of time tracking the uneven paths of its adult characters, Wildlife is ultimately about young Joe and how he survives the nuclear family meltdown. In that previously described scene where he stands in front of the wild fire, Dano’s camera eventually pans up to reveal a horizon choked with smoke and flames. Joe is scared, but he doesn’t run from it, instead choosing to observe it head-on. Unlike the emotional careening his mother and father engage in, Joe is probably the one who endures the most pain and comes out the other side a better (and more adjusted) individual.

Wildlife opens in the Dallas/Fort Worth area on Friday, November 2.